‘Debt trap' diplomacy is a card China seldom plays in Belt and Road initiative

It’s taken as a given that the Belt and Road initiative (BRI), China’s effort to close the world’s multitrillion-dollar infrastructure gap, is an attempt to extend Beijing’s influence throughout the world by means fair and foul. One of the most incendiary charges is that China uses BRI funds to overwhelm recipient nations, drown them in debt and then seize collateral, often strategic assets, such as mineral resources or a port. Excessive debt can be a problem, but it is not the product of a Chinese strategy. Instead, a combination of “need and greed” among creditors and recipients is to blame. Japan and other countries should focus on those enduring problems rather than BRI.

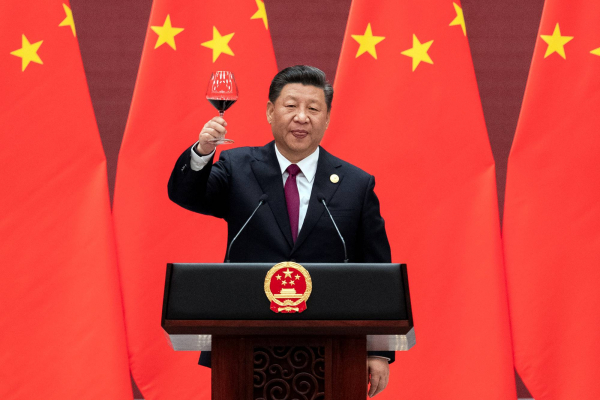

BRI was announced in 2013 and became supreme leader Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy project. In 2017, it was written into the constitution of the Chinese Communist Party and 138 countries and 30 international organizations have agreed to participate, with announced investments to link Asia, Africa and Europe reaching some $8 trillion.

While there have been grand multilateral events to celebrate BRI, much of its workings are bilateral, and investment contracts have been negotiated in secret. It isn’t clear which Chinese aid projects are linked to BRI. It appears to have become a portmanteau term that encompasses all of Beijing’s aid. Whatever the amount, BRI opacity has generated criticism.

One of the most powerful charges was launched by an Indian think tank that warned in 2017 about “debt trap diplomacy.” The meme exploded, generating nearly 2 million hits on Google within a year. When Sri Lanka defaulted on the contract to build Hambantota Port and a Chinese company got a 99-year lease in return, theoretical risk became real and the evidence of Beijing’s strategic designs pronounced clear for all to see. Fears grew when the Center for Global Development, a Washington think tank, warned that “23 of 68 countries benefiting from Belt and Road investments were significantly or highly vulnerable to debt distress,” and identified eight countries — Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Montenegro, the Maldives, Pakistan and Tajikistan — to be particularly at risk. The authors voiced “concern that debt problems will create an unfavorable degree of dependency on China as a creditor. Increasing debt, and China’s role in managing bilateral debt problems, has already exacerbated internal and bilateral tensions in some BRI countries.”

For all the hoopla, the Sri Lanka case was unique. Deborah Brautigam, a researcher at the Johns Hopkins’ China-Africa Research Initiative (SAIS-CARI), concluded that Port Hambantota is the only case, out of thousands of BRI projects, that could be called debt-trap diplomacy. And if Hambantota was a debt trap, China didn’t set it. A new study from Chatham House, the respected British think tank, blames Sri Lanka’s IMF bailout; Chinese investment was “not used to repay port-related debt, but to pay off more expensive loans, generally to Western entities.” In fact, virtually every study that looks at the terms of developing country debt sees developed country lending as more onerous than that of China.

When they examined Chinese loans to Malaysia, another country purported to have been crushed by BRI “generosity,” the Chatham House authors concluded that Chinese-backed projects “were overwhelmingly nonstrategic investments in the sectors of real estate, entertainment and industry, while port and railway projects were developed commercially by subnational actors on both sides.” In Africa, where BRI projects are thought to be especially predatory, a Brookings Institution analysis concluded that “borrowing from China is integrated into their overall debt and budget management.” It noted at least 140 instances of China restructuring or writing off lending practices that cost China money.

Australia’s Lowy Institute reached similar conclusions in its October 2019 study of BRI lending in the South Pacific. “The evidence suggests China has not been engaged in deliberate ‘debt trap’ diplomacy in the Pacific.” After examining BRI projects in Southeast Asia, the U.S.-based Asia Society Policy Institute was skeptical of China’s laissez-faire attitude toward lending and warned of unsustainable debt. Yet it too acknowledged that China has renegotiated onerous contracts and adjusted to new realities. In other words, the “pattern of flexible response to debt, including limited write-offs (applying only to zero-interest loans), and in some cases, delaying payment, rescheduling or restructuring” identified in the SAIS-CARI study appears throughout the BRI.

Not surprisingly, a reassessment is underway. The Chatham House authors argue that “China cannot and does not dictate unilaterally in the name of BRI.” Instead, BRI projects develop through negotiations between China and recipients, “co-created through countless, fragmented interactions.” The rest of the world should “stop responding to the BRI as though it were a well-planned grand strategy and recognize it for what it is: an often fragmented, messy and poorly governed set of development projects.”

Don’t blame Beijing if projects don’t work or unfairly burden recipient countries. The Chatham House analysis blames the economic logic guiding the state-owned enterprises behind many BRI projects: They are trying to make money at a time of domestic overcapacity, which pushes them into overseas markets.

Nevertheless, Elaine Dezenski, an anti-corruption expert, sees a vital connection between supercharged Chinese capitalism and large-scale corruption. In “Below the Belt and Road: Corruption and Illicit Dealings in China’s Global Infrastructure,” a new study for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, she argues that BRI exports “corruption, opacity, and waste,” “features (that) are not incidental side effects of working in countries where graft is endemic, but rather an upside for China.”

The chief enabler is China’s commitment to “noninterference” in the domestic affairs of other countries. This is intended as a stark contrast to the readiness of Western governments to tell recipient nations how to run their countries. Consistent with that principle, Beijing puts “no economic or political conditionalities on funding” — like transparency. The result is BRI projects that are “riddled with graft, influence peddling, and embezzlement. The unstated purpose of noninterference is to provide cover for such practices.” Why not? Chinese companies benefit from the business, China gets credit for the loans and local constituencies favorable to Chinese interests and outlook are empowered.

But, this advantage is fleeting. Revelations about corruption threaten an anti-China backlash that undermines hopes of using BRI to expand Beijing’s geopolitical influence. Intense scrutiny has forced renegotiation and greater attention to potential Chinese abuses.

Stung by criticism, China pledged to create a Clean BRI in 2019 and preliminary evidence suggests that Beijing is trying to improve lending practices. In a study published earlier this year, the Rhodium Group, whose China work is always worth reading, argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has forced China to renegotiate loans, which bolsters its image as a development partner. Last weekend, China announced that it had, as part of a G20 standstill program, struck agreements with half of the 20 low-income countries that requested debt restructuring as part of their response to the COVID outbreak.

BRI demands a more subtle and nuanced response. Exaggerating dangers as Beijing tries to address a real need will only discredit critics and make China’s job easier. BRI responds to a genuine need in the developing world and China has shown a knack for learning from its mistakes. Done properly, a massive investment project will spread influence and project power. Countries such as Japan, the United States and Australia should be engaged as well, providing funds of course, but also by developing and enforcing a framework that ensures that assistance works as intended. Japan, the U.S. and Australia have taken steps in this direction with the Blue Dot Network, a stamp of approval on infrastructure projects that ensures that they are consistent with global standards for good governance. Dezenski urged Blue Dot Participants to build in the new ISO 37001 anti-bribery management system standard, which more than 35 countries, China and the U.S. among them, helped develop. Good governance, the cornerstone of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific, is always the right focus.

Sep 1, 2020